John Joseph Enneking. Sheep by a Pond (Grew’s Woods, Hyde Park, MA), 1890. Oil on canvas. Collection of the Cahoon Museum of American Art.

John J. Enneking was the subject of the first exhibition I curated at a non-academic museum. Pinpointed—thanks to an otherwise inconsequential sketch of Claude Monet’s first wife, Madame Camille Doncieux Monet—as the first American Impressionist. The sketch, made in 1873, predated the Impressionists’ debut exhibition by approximately one year. The Enneking exhibition that I curated was an exciting opportunity at a time in my life marked by precarity and uncertainty.

When I first began the project, I had just moved from a small college town in southern Wisconsin to Cape Cod—living long-term outside of the Midwest for the first time in my life. As I finished my research and writing for the exhibition, Trump was elected and sworn into office for his second term, and the repercussions of his first few months in office were felt deeply by those across the country, including myself and my colleagues working in museums. What a time, I thought (and continue to think), to be a curator of American art. America, ever a contentious territory, concept, and category—ever a precarious (sub)-field to be working in.

I officially arrived on Cape Cod in July, when vacationers and summer-dwellers had swelled the population to quadruple its usual size, and I spent hours in gridlock on rural roads bookended to my left by the bay and small, sandy forests on my right. The trees were one of the first things I noticed upon first arriving on the Cape, and I spent vast expanses of my late afternoons inching slowly over the hill just beyond the Sagamore Bridge, taking long looks at where the branches raked the sky.

The trees in New England—and specifically on the Cape—aren’t like the ones in the Midwest. In Ohio, the soil is dark and cold—at least it is where I had lived. There, on the edge of the Ohio River, on the western border of Appalachia, the roots grope deeply, firmly, into the earth. But the trees of Cape Cod grasp at sand, growing somewhat tall and extremely lean. I’m sure Enneking would have taken notice of this as well when he transitioned from rural Ohio (and later Cincinnati—then known as “The Queen City”) to Boston, painting his way up the East Coast.

Charles Magnus (1826-1900). Bird’s-Eye View of Cincinnati, 1850. Chromolithograph. Image courtesy of the Chalmers Library at Kenyon College, Long-term Loan from the Estate of Boris Blick, 2015. 2015.3.

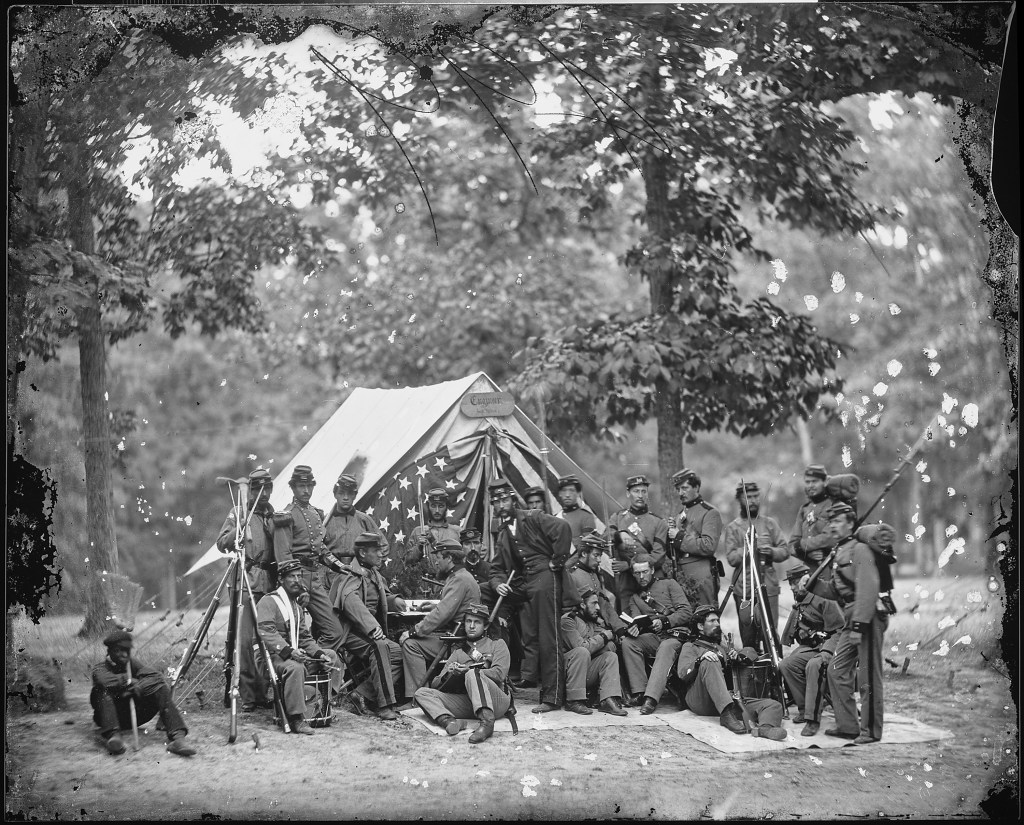

But before Enneking made his way to Boston (by way of New York), he served in the Union Army. There are varying accounts of this service, including everything from his capture by the enemy, his sketching on his bandages while in recovery, his refusal to faint when administered anesthetics due to his concerns over being perceived as effeminate and thereby almost dying due to loss of blood. There is, however, general consensus that he enlisted energetically, was wounded less than a year into his service, and was thereby discharged. Regarding Enneking’s enlistment, his vigor is accounted for by his deep moral opposition to the institution of slavery. As a documented member of one of Boston’s Unitarian churches later in life and the son of German immigrants, Enneking was headstrong in his personal beliefs, exhibited in his painting career.

Despite the varying accounts of Ennekings personal life—with there even having been some discretion on his birth year, as is to be understood given he was likely given birth in relative solitude on his family’s farm—he is a highly compelling individual, at least for myself. The fact that even his status as America’s first Impressionist lacks the degree of celebration and documentation that one would expect of an artist with such a title. Perhaps most interesting, however, is how Enneking seemingly straddled so many American twilights.

Engineer camp, 8th N.Y. State Militia. The creator compiled or maintained the parent series, Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, between 1921–1940. Courtesy of the National Archives.

His later involvement with the plein air painters of Europe as well as his own commitment to painting outdoors, directly from nature, was in opposition to the newly accessible practice of photography. Never a “copyist or a camera,” as he stated, Enneking largely resisted the pull of photographic references. This is not to say that he didn’t participate in photography. In fact, there are photographs, although amateurish, attributed to Enneking. Indeed, it is likely that Enneking made use of photographs to complete larger works after bringing them home from his outdoor sessions or to study for future projects as many artists did. But the Barbizons and Impressionists he studied with throughout Europe doubtless imparted their drive to work en plein air. While Enneking remained highly selective regarding his mentors’ espousals, this is clearly one that he wholeheartedly adopted, and it is definitional of both the Impressionist and earlier Barbizon movements.

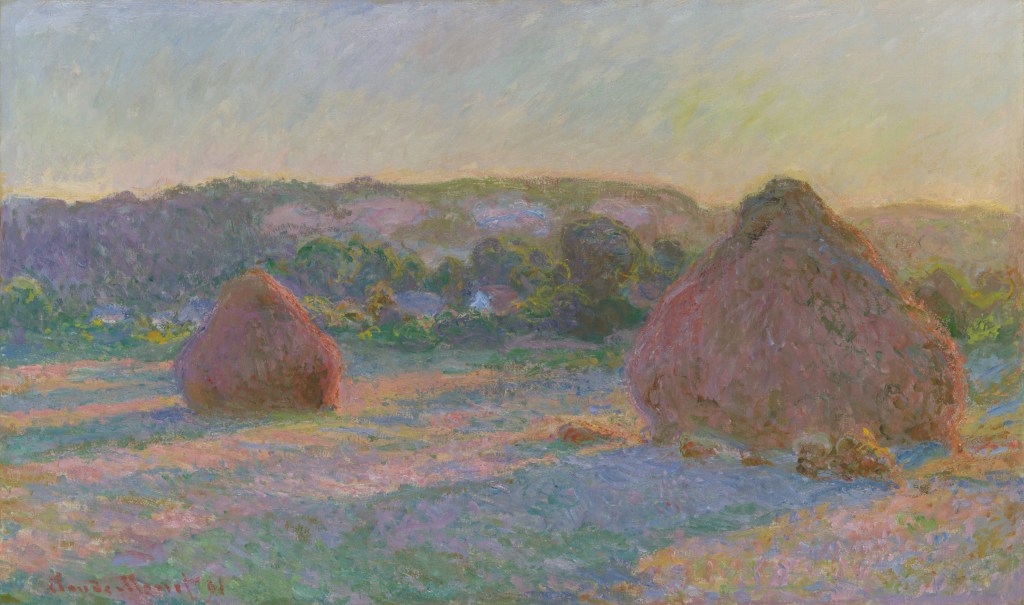

Claude Monet. Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer), 1890-1891. Oil on canvas. Gift of Arthur M. Wood, Sr. in memory of Pauline Palmer Wood. The Art Institute of Chicago. 1985.1103.

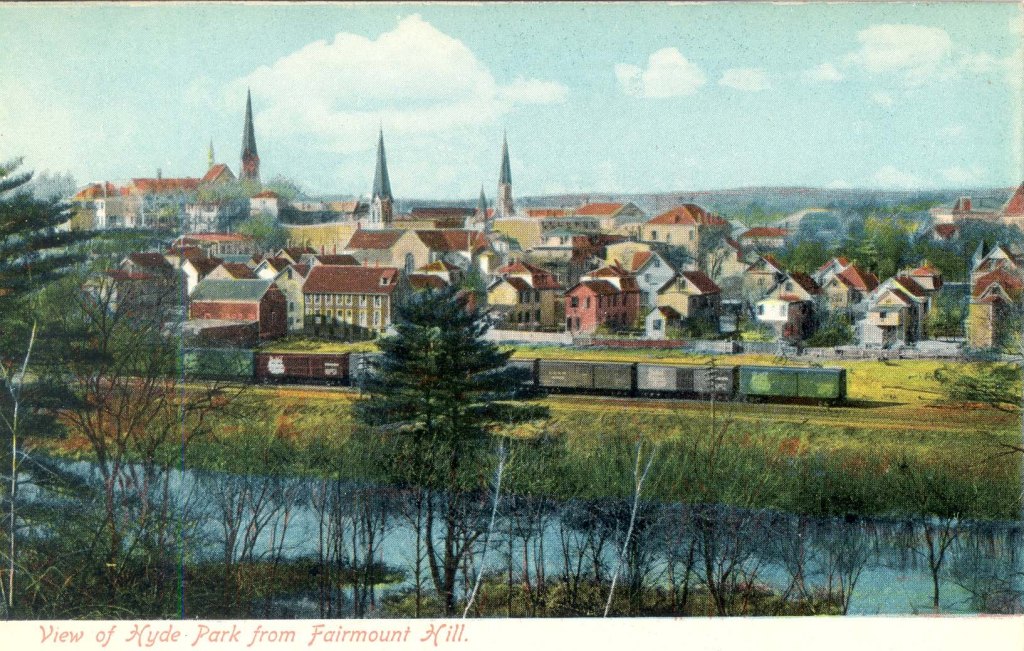

When Enneking married and moved to Hyde Park, the fledgling town had just been incorporated. Though Enneking traveled throughout Europe, painting in Italy, Germany, and Holland, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and France, he maintained a certain American-ness about him. And, in a way, he was a forerunner of this very American-ness in art. In Europe, he studied with the pioneers and precursors of the Impressionist movement including Claude Monet as well as Munich Academy artists Eduard Schleich The Elder (1812-1874) landscape specialist Adolph-Heinrich Lier (1826-1882), Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), Barbizon school painter Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), and plein air pioneer Eugene Boudin, respectfully. In addition to painting alongside Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Edouard Manet (1832-1883), and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), his closest contemporaries were realist painters Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875) and Jean-François Millet (1814-1875). Interestingly, both men would have been in the final years of their lives during Enneking’s pivotal study abroad. Both Corot and Millet imparted lifetimes of artistic knowledge unto the studious Enneking, and Enneking—an American outsider—therefore made his way into the gardens, harbors, and inner-worlds of the Europe’s artistic circles, straddling a gap between countries, generations, and movements over the course of his multiple European voyages.

Left: View of Hyde Park from Fairmont Hill. Image courtesy of the Hyde Park Historical Society.

Right: John Joseph Enneking. Boston Commons and the State House, n.d. Oil on board. Cape Cod Museum of Art Permanent Collection Gift of Professor Morris Cohen, 2006 2006.8.14.

Due to his prolific portfolio, it is clear that Enneking took on many American subjects. He traveled throughout the Northeast region, portraying its hills, valleys, mountains, structures, brooks, harbors, and vast skies. But Enneking’s preferred American subjects—foremost the New England twilight in autumn—was not the only element which made Enneking not only an Impressionist, but an American Impressionist. It can also be seen in his color palette which deviates from the vibrating pastel tones of the French Impressionists. In many of his works, Enneking’s palette takes on the tones reminiscent of many of the foremost American painters of his era. His colors privilege realism and are beautiful without being decorative.

Isaac Henry Caliga (1857-1944), a contemporary of Enneking, depicted him here as he looked in his early years. His dark suit is indicative of men’s fashions of the time. Caliga took care to render Enneking’s long reddish-brown beard, a signature visual feature and lifelong staple for Enneking’s appearance. His gaze is not deterred by the confines of the canvas. His blue-grey eyes gaze intently toward some distant scene or ideal. His arm, like a sturdy trunk, is rooted into his side. Here, Enneking is determined, strong, and thoughtful. He poses with his brush, palette, and a rag—the tools of his trade.

Isaac Henry Caliga. Portrait of John J. Enneking, 1884. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Hyde Park Branch of the Boston Public Library.

In Caliga’s portrait, Enneking’s palette is smeared with a large quantity of orange paint, referencing the artists’ favorite subject of New England twilight. The color has taken up much of the space provided, indicating the care Enneking took in mixing the vibrant hues of his preferred scene. Caliga has enlivened the background with this same orange, glowing against an artist dedicated to making his own way in the burgeoning world of American art. In his later years, much like Monet, Enneking would attempt to flatten the picture lane of his landscape, veering toward a more abstracted use of color, brush, and knifework.

Twilight, interestingly, refers to both sunrise and sunset, beginning and end, birth and death of the new and old day. Enneking, in both his personal and professional life, saw his fair share of beginnings and ends—and actively participated in them as well, from being orphaned and suddenly transplanted from a rural farm to one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States to his involvement in the Civil War at a time when the country felt itself being torn apart, to his contributions to a truly American style of painting. Enneking stood again and again at the brink, working—in his own way—toward his own ideals. Despite the lack of scholarship and general conversation around his work, that is perhaps the most American thing about him. In times of trouble, he slammed his body against the rudder and steered toward his own unique destiny. Who’s to say he himself knew where he was headed or how his legacy would be maintained, if he considered it at all. But there is an earnestness to his efforts, a bold intentionality to his brushwork, and an astounding sense of vision as he gazed toward a horizon not yet visible to seemingly anyone but himself. It is this quality that not only made his work so enigmatic to me during my research, but sustained me during a tumultuous New England twilight of my own.

Left: John Joseph Enneking. Autumn Sunset, 1895. Oil on canvas. Gift of Herbert W. Plimpton: The Hollis W. Plimpton (Class of 1915) Memorial Collection. Mead Art Museum at Amherst College. AC 1971.58.

Right: John Joseph Enneking. Fiery Sunset, N.d. Oil on canvas. Collection of the Cape Cod Museum of Art. 2006.8.17.

Leave a comment