On May 15, 1936, Harry Sternberg’s six-month tenure as a Guggenheim fellow began. He applied with the intention of producing etching and lithographic work, which he completed throughout his subsequent travels throughout Eastern Pennsylvania. His subjects of choice for the project were a rotating cast of men from the coal and steel industries, whose working conditions and general quality of life he recorded through drawings and prints. Over the months, he came to know the workers personally through late-night trips to the bar and accompanying them into abandoned mines. While his motivation to represent the workers of these industries is often given precedence in describing the significance of this era of his work, there is a second—equally if not more important—layer to the series: his unknowing role in the documentation of the final years of company towns.

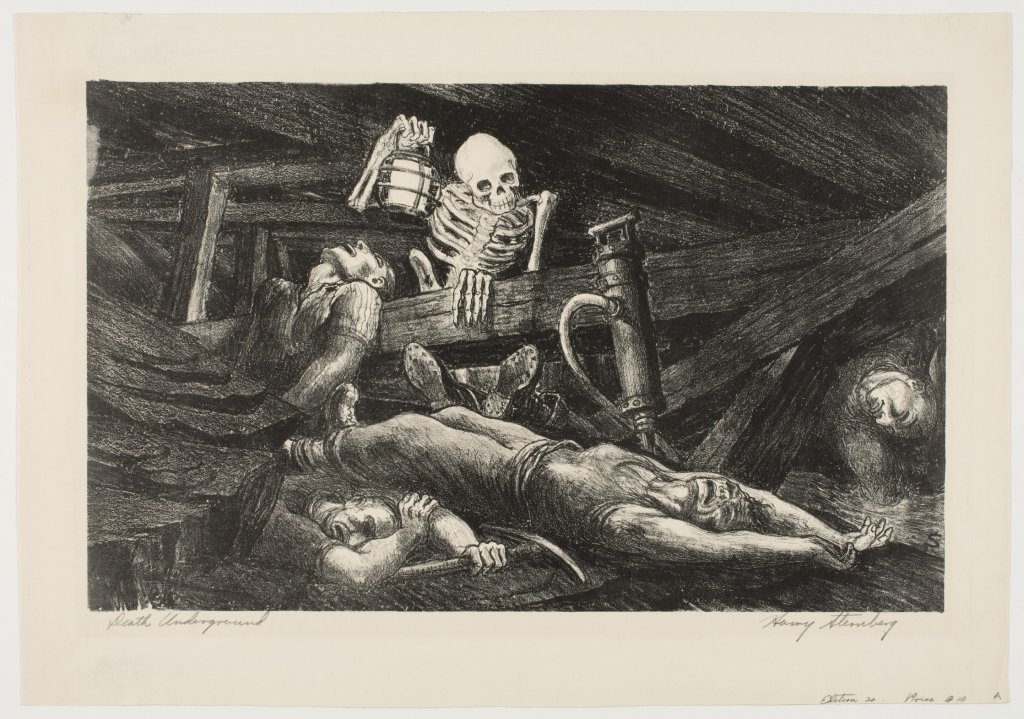

Harry Sternberg (American, 1904 – 2002). Death Underground, 1934. Lithograph. Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Art Museum. Courtesy of the Estate of the artist and Susan Teller Gallery, NY, NY. 1972-24-93.

His studies in America’s steel and coal communities were informed by his previous year’s position as a technical advisor to the Federal Art Project’s Graphic Art Division of the newly-established Works Progress Administration. Additionally, his work with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo just two years prior to the start of his fellowship informed his political considerations, leading him to become active in Leftist causes including the Congress of Industrial Workers (CIO) based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was with this perspective that he approached the American industrial landscape and the workers who populated it.

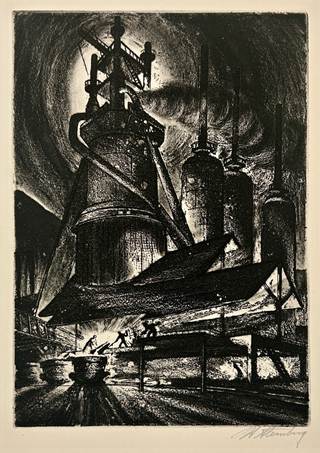

Harry Sternberg (American, 1904 – 2002). Steel Town, 1937. Lithograph. Image courtesy of the Block Museum, Northwestern University. 1995.37.

Sternberg’s Steel Town illustrates the overwhelming presence of industry in a company town. The blast furnace towers over the church which, in turn, dwarfs the ramshackle company housing. Several dark figures roams the streets compositionally positioned above the final resting place of the workers whose headstones are equally indiscriminate as the shadowy figures populating the town. There is an egalitarian anonymity afforded to the workers, while the hierarchy of machinery over man—over God Himself—is made evident in the composition. Having spent several months living in a coal-company owned town, Sternberg later reflected on its “bleak” landscape and barren economic prospects:

The houses hadn’t been painted; they were company houses. And it was a depressed time. It was a depressed time. Guys were hungry, angry—angry at the church, incidentally. The Catholic Church dominated this area, too. And one of the miners, I well remember him saying, “Never again to church for me. The preacher came in and wanted some money for the church, and I said, ‘I don’t have milk for my kids.’” But they literally didn’t have money for the iceboxes, a cake of ice on the top.1

Company towns often functioned in this way and were common among coal, steel, and other similar industries. When men took jobs that required long hours on-site in relatively remote locations, company towns were the solution for cheap housing. Allowing the owning class essentially total control over their workers and their families, the towns often had paternalistic functions as well, socially molding the ideal modern worker in the company-built mines, factories, churches, schools, and houses. Even local businesses, like the store advertising beer in Steel Town, were usually monopolies, feeding all profits back to the company. The miniature Capitalistic dictatorship model which the towns ran on—and which was clearly unpopular with workers—coupled with increasing pressure from Roosevelt’s New Deal policies regarding minimum wage and other employee advocacy eventually led to their demise.2

Left: Harry Sternberg (American, 1904 – 2001). Blast Furnace #1. 1937 (published 1946). Etching and aquatint in black on wove paper. Corcoran Collection (Bequest of Frank B. Bristow). 2015.19.1400. Image courtesy of Childs Gallery, Boston.

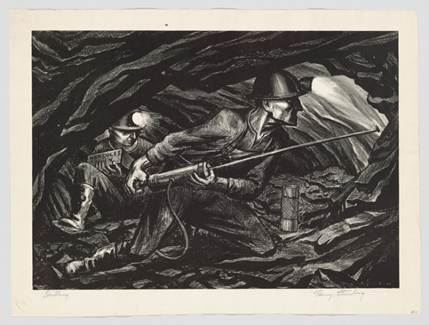

Right: Harry Sternberg (American, 1904 – 2001). Drilling, 1936. Lithograph. 96.68.293. Image courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from The Lauder Foundation, Leonard and Evelyn Lauder Fund.

The images from the steel and coal series are monochromatic with dramatic swaths of dark ink. Oftentimes, the only source of light was a blazing fire of a blast furnace or the single light at the top of a miner’s headlamp. Regarding the visually dark images that emerged from the steel and coal series, Sternberg remarked

That blackness is inevitable. You go down in a coal mine, and if you’re alone, you cover the lamp, you’ve never seen blackness like it. Several hundred feet underground, and there’s no source of any reflection, of any kind: it’s black. It’s disconcerting, you know, the notion of getting caught in that kind of blackness. And there are rats—you hear them scuffling, and you see them occasionally.3

Sternberg’s advocacy for the workers was seen through his earnest, though at times naïve, impulse to observe the miners’ dangerous working conditions first-hand. His dedication to documenting the hazards they experienced on a daily basis led him from the hottest furnaces of the steel mills to the coldest depths of the earth and back again:

There was one coal mine that had been flooded because it caught fire. It was out of use. I wanted to get in and see the inside of this mine after what had happened. And this young buddy, whom I drank with all the time, went down with me. It took a lot of persuading and a lot of booze to get him to say he’d take me in. He didn’t like it. I was probably dumb enough not to realize the danger. But you wandered in there and you saw what black was.4

Harry Sternberg (American, 1904 – 2001). Coal Miners. ca. 1936-1937. Crayon and aquatint on paper. Image courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. 1998.125. Copyright Estate of Harry Sternberg.

Harry Sternberg passed away in Escondido, California, on November 27, 2001 at the age of 97 having witnessed not only the death of company towns, but the deindustrialization of the United States throughout the latter half of the 20th century—the second death of these industries. Despite the deadly working conditions and overall grim outlook of their work, Sternberg praised the men he lived amongst for the six months of his documentarian work, reflecting fondly, “And they were very hospitable. It was a wonderful period. It’s like the Lower East Side. It was juicy and alive, noisy, dirty, but so alive. Everybody was fighting and arguing and pushing and yelling and talking at once. Nothing polite about it. But, oh boy, it was alive.”5

- Harry Sternberg, interview by Sally Yard, Archives of American Art, March 19, 1999-January 7, 2000. ↩︎

- Margaret Crawford, Building the Workingman’s Paradise: The Design of American Company Towns (Verso, 1995). ↩︎

- Harry Sternberg, interview by Sally Yard. ↩︎

- Harry Sternberg, interview by Sally Yard. ↩︎

- Harry Sternberg, interview by Sally Yard. ↩︎

Leave a comment